1987 - Cason

| Year | 1987 |

| Vessel | Cason |

| Location | Off North Spain |

| Cargo type | Package |

| Chemicals | CRESOLS (ortho, meta, para) , DIPHENYLMETHANE-4,4'-DIISOCYANATE , FORMALDEHYDE flammable solutions , SODIUM metal |

Summary

At 04.55 hours on December 5, 1987, the cargo ship Cason, flying the Panamanian flag, navigating in heavy weather close to the Spanish north-west coastline near Cape Finisterre on a voyage from Antwerp to Shanghai, sent a distress message reporting that there was a fire on board and requested assistance. At 05.55 hours, it was reported that the fire was out of control, the ship was being abandoned and the crew was taking to the lifeboats. Rescue services, including three helicopters, one tug, rescue launches and ships navigating in the area were immediately mobilized. Only eight of the 31-man crew were saved.

During the first few hours of rescue operations, no one had any idea of the range of dangerous goods onboard. All that the emergency team knew from the hazard warning labels they had seen on some of the containers and drummed cargoes stowed on deck was that there were some flammable and toxic substances onboard. The rescued crew were also not very co-operative with the authorities so that very little, if any, information could be obtained from them.

After recovery of the survivors and bodies, the rescue tug tried to bring the vessel on tow and keep her from the rocks but the bad weather and the fire which continued on board made the operation difficult and eventually the wind drove the ship aground where she stranded on the coast near Cape Finisterre.

During the next day, December 6, the situation was calm with the ship laying stranded and some smoke coming out of its holds. The press reported on the rescue operation. In the meantime, efforts were being made to provide the Spanish maritime administration with detailed information on the ship's cargo and its stowage by the EEC Task Force and by the maritime authorities of the ports of Hamburg, Rotterdam and Antwerp.

On the morning of December 7, the national maritime authority in Madrid activated the national contingency plan. Information on the identification of the cargo and its location onboard reached the authorities by the afternoon. This was passed on to the media who by then had already begun to speculate and create alarm among the local population.

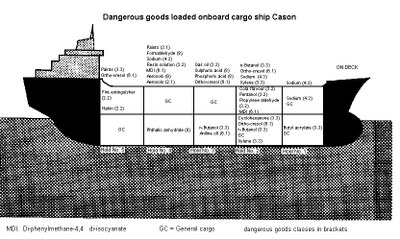

After having reviewed the dangerous goods list and the way the goods were stowed onboard the Cason (Figure 1), an analysis of the situation was made of the situation and the salvage and pollution prevention operation planned.

Narrative

At 04.55 hours on December 5, 1987, the cargo ship Cason, flying the Panamanian flag, navigating in heavy weather close to the Spanish north-west coastline near Cape Finisterre on a voyage from Antwerp to Shanghai, sent a distress message reporting that there was a fire on board and requested assistance. At 05.55 hours, it was reported that the fire was out of control, the ship was being abandoned and the crew was taking to the lifeboats. Rescue services, including three helicopters, one tug, rescue launches and ships navigating in the area were immediately mobilized. Only eight of the 31-man crew were saved.

During the first few hours of rescue operations, no one had any idea of the range of dangerous goods onboard. All that the emergency team knew from the hazard warning labels they had seen on some of the containers and drummed cargoes stowed on deck was that there were some flammable and toxic substances onboard. The rescued crew were also not very co-operative with the authorities so that very little, if any, information could be obtained from them.

After recovery of the survivors and bodies, the rescue tug tried to bring the vessel on tow and keep her from the rocks but the bad weather and the fire which continued on board made the operation difficult and eventually the wind drove the ship aground where she stranded on the coast near Cape Finisterre.

During the next day, December 6, the situation was calm with the ship laying stranded and some smoke coming out of its holds. The press reported on the rescue operation. In the meantime, efforts were being made to provide the Spanish maritime administration with detailed information on the ship's cargo and its stowage by the EEC Task Force and by the maritime authorities of the ports of Hamburg, Rotterdam and Antwerp.

On the morning of December 7, the national maritime authority in Madrid activated the national contingency plan. Information on the identification of the cargo and its location onboard reached the authorities by the afternoon. This was passed on to the media who by then had already begun to speculate and create alarm among the local population.

After having reviewed the dangerous goods list and the way the goods were stowed onboard the Cason (Figure 1), an analysis of the situation was made of the situation and the salvage and pollution prevention operation planned.

Resume

The ship was aground at a distance of about 100 metres from the shore in a rocky area and almost the whole of the ship's bottom was damaged. Water was flooding into all the cargo holds as well as the engine room space. Re-floating under these circumstances would have been exceedingly difficult. Smoke was observed coming out from holds 1 and 2, although there were no visible fires and small quantities of fuel oil were spilling into the sea.

Following assessment of the chemicals using the GESAMP profiles, the main threat of chemical pollution came from cargoes of aniline oil, ortho-cresol and di-phenylmethane-4, 4 di-isocyanate (MDI). The IMDG Code lists these three substances as 6.1 (toxic) substances, but only ortho-cresol is also classified as a "marine pollutant". The remaining substances were flammable or corrosive and, with the exception of the ship's fuel, these presented little threat to the marine environment.

However, of all the cargoes, the containerized drums of sodium metal (Class 4.3) presented the greatest threat. The Cason carried 11 containers: 1,430 drums totalling 126 tons of sodium. Sodium is a metal that floats and reacts violently with water or moisture to produce highly flammable hydrogen which may auto-ignite during the process. It is also corrosive to the skin and eyes.

After carrying out an onboard survey, the following plan of action was prepared:

1. discharge of sodium from the deck;

2. discharge the sodium from hold No. 1;

3. unload the dangerous goods located on the deck in the following order of priority: ortho-cresol, MDI, formaldehyde, phosphoric and sulphuric acids, the remaining goods;

4. transfer the bunker fuel;

5. unload the goods from the holds beginning with the most dangerous.

Four salvage vessels equipped for combating pollution, as well as other auxiliary vessels, were initially available for the operation. Arrangements were also made for the provision of large cranes from Dutch Salvage companies but the experts from the salvage companies were not expected to arrive before the evening of December 10 and the heavy lifting equipment not before December 14.

During December 8, 9 and 10, while awaiting the arrival of heavy lifting equipment for the unloading of sodium, 204 drums of ortho-cresol and 29 of formaldehyde were offloaded. However, bad weather made it necessary to suspend operations.

During the following days from December 10 onwards, drums of sodium were broken open by wave action and reacted violently with the water. These explosions occurred along the entire length of the ship since the sodium was stowed above more than one hold. The reactions also caused the fire to spread to the other flammable goods and during December 10 and 11, the whole deck of the vessel sustained fires and explosions (Figure 2). Sodium-fuelled reactions were also seen at sea as drums had fallen into the sea during the accident.

By December 10 and 11, journalists had arrived in nearby towns and the news and speculation in both the national and local media created alarm among the population. Although efforts were made by the authorities to explain that there was no immediate threat (the people living closest were 6km from the accident), the hysteria and panic generated by the news media forced the authorities to decide on evacuating the area. The Civil Protection Services and other local authorities organized the evacuation. This was organized late at night and 300 buses were dispatched to the area and information given by local radio on how to leave the area and the direction to go in order to avoid the "toxic cloud". This created more confusion and people abandoned the towns using their own mode of transport or on foot. Telephone lines were also blocked as people sought information. Eventually, people were placed in shelters whilst hotels were put on standby. The army was also sent in just in case problems arose with crowd control. As the evacuation of people took place, the events leading to the sodium generated fires and explosions were also taking place. This coincidence of events contributed to further alarming the local population. After 2 - 3 days, people returned to their homes but problems with public relations continued.

By December 12, all the sodium had reacted and the fire put out by the waves. The sea state made it possible for an inspection to be carried out to verify that no toxic gases were being released, that all the sodium had reacted with water and the holds were flooded with water.

The original salvage plan of unloading the dangerous goods in order of priority was reactivated. A large floating crane had been positioned nearby the stranded vessel, as well as a barge for the storage of recovered cargo, the latter supported by two other vessels (Figure 3). Bad weather slowed progress but during December 19 and 20, a total of 21 containers and small quantities of drums and cases were recovered. Many drums were thrown into the sea by the wave action and floated onto the beaches. It was therefore necessary to set up a location for identification and recovery in case any of the drums contained dangerous goods.

Thereafter, about seven weeks of bad weather hampered the salvage work considerably and these periods were used for offloading part of the fuel since it was only occasionally possible to work on the recovery of the cargo.

From February 18, 1988 onwards, the weather improved and it was possible to work more or less continuously. The dangerous cargo was recovered, although great technical difficulties were experienced in unloading the drums stowed below deck as the fire and the action of the heavy seas had moved the general cargo haphazardly. This blocked access to the dangerous cargo. It was decided to use a large crane equipped with a grab which was capable of tearing the ship's deck and sides apart. This allows getting at the dangerous goods.

When most of the dangerous cargo was recovered, the aniline oil still remained onboard since this was stowed in the lower holds which were inaccessible. Finally, after removal of the hold's deck, it was possible to recover this dangerous cargo. On March 12, the work of recovering the dangerous goods from the vessel was regarded as complete, although the area continued to be monitored in order to identify any drums which had been swept overboard by the waves as well as to determine the effects of oil pollution from the fuel and engine oil residues.

In spite of the spectacular nature of the operations, no fatality occurred: three persons were slightly injured and one showed symptoms of slight aniline poisoning.

At the start of the salvage operations, a monitoring plan for sea and air pollution was set up.

For air pollution, a network for air detection was established. No significant air contamination was detected. During the days when the sodium reacted with sea water, large white vapour plumes were observed; for the most part, these were made up of water vapour, although the white plumes alarmed the public.

Pollution of the sea never reached high concentrations because both the fuel and the chemicals were spilled intermittently and in small quantities. Nevertheless, as a prevention measure, a moratorium of fishing took place at a radius of 10 miles from the shipwreck. Even though fishing was allowed in other areas, the people living in the Galicia region refrained from buying fish. This had an economic impact on the livelihood of fishermen.

During the days of particularly bad weather, a number of dark yellow slicks formed in areas not more than a mile away from the ship. These slicks, formed as a result of leakage from damaged drums, gave off an odour of chemicals and looked like a "lemon mousse", probably the result of a fuel-chemical cocktail. However, they did not appear to give off toxic vapours as was confirmed by chemical analysis and also by the presence of sea birds which were seen flying over the area without being affected. It was not possible to recover the spilled substances because of the severe storms and the fact that boats were prevented from working in the high waves and the proximity of the breakers to the shore. Because of the strong wave action, the "mousse" naturally dispersed within one or two days.

Chemical analysis of the first seawater samples gave negative results indicating that even if certain quantities of substances were present, they were at such a low concentration that they could not be detected. Analytical results throughout December and January showed that, for the most part, traces of pollutants in the sea remained negligible. Only occasionally did appreciable concentrations occur in samples within a mile of the ship. This was due to the rupture of a drum caused by heavy weather. For example, on January 14, 11 to 25ppm of ortho-cresol were detected as well as minute traces of aniline and xylols. Analysis of fish and shellfish showed no long-term damaging effects.

Problems arose in the disposal of drums containing the dangerous cargo. Residents in nearby port areas, provoked by certain organizations which created alarm on the possible human health effects, did not allow temporary storage of these drums in the nearby port areas. The authorities therefore decided to send the drum to the "Alumina Espanola" factory in the vicinity of the port of San Ciprian. However, the residents of a village situated en route to the San Ciprian port intercepted the lorries and police had to intervene. The drums were eventually sent to a military site.

In the following days, provoked by the alarmist information generated by certain organizations and the media, the local population and workers from the "Alumina Espanola" factory demonstrated against the authorities who had decided that the drums should be transported by ship from the port of San Ciprian back to Rotterdam, the port origin of the cargo. The problem was eventually solved (months) but not before the production at the factory was brought to a standstill by worker strikes which paralyzed the electrolytic process for the production of aluminium.

Finally, although spillages occurred as a result of packages being broken open by wave action, water pollution never reached high concentrations. This is because the spillages took place intermittently, the quantities released were small, and because they were diluted and dispersed by the action of the sea which was, for the most part, very rough in the area of the casualty.

The Spanish authorities felt vindicated that their persistent efforts to remove Cason's cargo over a long period helped to minimize what could have been a major case of marine pollution. At one stage, both the hull and P&I insurers of the cargo advised the Spanish government against struggling on with salvage operations during the long winter months. They argued that once the sodium fires were out, it would have been better to leave the wreck until the spring at which time clean-up operations could have proceeded much more quickly and at less cost.

The Spanish authorities however contended that the stowage arrangement of dangerous goods in the holds of the Cason added considerably to the difficulties of recovery. They further agreed that this slow progress meant that the cargo would have to stay onboard longer and the longer dangerous substances remain on a vessel, the greater the likelihood of pollution.