2000 - Ievoli Sun

| Year | 2000 |

| Vessel | Ievoli Sun |

| Location | Off the Channel Island of Alderney, UK |

| Cargo type | Bulk |

| Chemicals | STYRENE MONOMER inhibited |

Summary

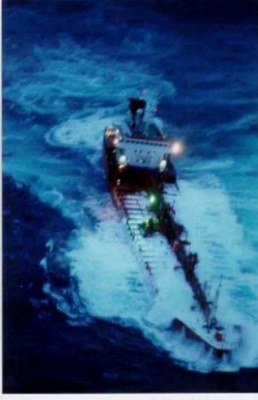

The Italian chemical tanker Ievoli Sun left the British port of Fawley for Bar in Yugoslavia, carrying 6,000 tons of chemicals, including 3,998 tons of styrene, 1,027 tons of methyl ethyl ketone and 996 tons of isopropyl alcohol. On 30 October, in stormy weather, the vessel developed a list on its port side and its bow began to dip into the sea (Figure 1). At 08.00 hours, the 14-member crew (12 Italians and 2 Spaniards) were ferried to safety by a helicopter of the French Navy. A French tug was sent out to assist the abandoned vessel but could not get the tanker through heavy seas. The vessel sank in 60 - 80 metres of water, 18 km north-west of the Channel Island of Alderney, five hours before it was expected to reach the French port of Cherbourg (Figures 2, 3).

The ship was a 7,308 dwt double-hull chemical carrier fitted with 18 steel cargo tanks having a volume of 7,277 cu. m. The ship was built in 1989 and is registered in Italy, classed and operated by an Italian classification society and operated by an Italian company. During its life, the vessel had never changed flag.

The last expanded inspection had been carried out on 26 October 2000 and resulted in a detention of 3 days due to deficiencies related to the radio certification, lifesaving appliances, fire pumps and ISM Code implementation. None of these defective items were considered by the port state authorities as related to the classification society's responsibility.

Of the three products, styrene monomer is the chemical of most concern. Styrene is a colourless, oily, flammable liquid which has a sweet odour when pure and a sharp, disagreeable odour when impure. Like many monomers, styrene monomer is an extremely reactive and sometimes extremely unstable hazardous material that must be handled very carefully. Styrene can begin a potentially dangerous process called polymerization. In controlled polymerization, the liquid solidifies, expanding to about five times its original volume. Uncontrolled polymerization or "run-away polymerization" in a tank can be a violent exothermal reaction, powerful enough to rupture the tank, or in the extreme case, even burst the vessel, in a tank ship.

Styrene polymerizes at explosive rates at temperatures above 65ºC, a phenomenon which can cause the tank to rupture. Certain contaminants will readily form peroxides which, in turn, catalyze the polymerization reaction. To prevent this from happening, shipboard cargoes are usually stabilized with 10 to 15 parts per million (ppm) of an inhibitor called tertiary butyl catechol (TBC). However, even with the addition of an inhibitor, when heated above 51ºC, styrene can polymerize with the generation of so much heat that ignition is possible. A ship must therefore possess an inhibitor certificate before loading commences. This certificate indicates the amount and name of the inhibitor that has been added to the styrene monomer cargo; the date the inhibitor was added and its effective lifetime; any temperature limitations qualifying the inhibitor's effective lifetime; and details of action to be taken should the voyage length exceed the inhibitor's lifetime.

Due to its low electrical conductivity, styrene monomer can generate electrostatic charges when subject to agitation or particularly high flow rates. The substance reacts violently with strong oxidants and may be absorbed into the body by inhalation, ingestion or through the skin. It irritates the eyes, skin and respiratory tract, and, in liquid form, degreases the skin. Styrene is also harmful to aquatic life, having a 96hr-LC50 between 1 - 10mg/l. However, it is not a substance considered to bioaccumulate, but there is evidence to suggest that it will taint marine organisms.

The other two substances were methyl ethyl ketone and isopropyl alcohol. Methyl ethyl ketone is classified "D" according to the MARPOL 73/78 classification, i.e. if discharged into the sea, it would present a recognizable hazard to the marine environment. Isopropyl alcohol is classified "Class III", a flammable liquid, which is not considered toxic to the marine environment.

Furthermore, the tanker was carrying 160 tons of intermediate fuel oil and 40 tons of diesel. In case of leaks from the vessel, the fuel would probably form a slick that could contaminate the marine environment.

Narrative

The Italian chemical tanker Ievoli Sun left the British port of Fawley for Bar in Yugoslavia, carrying 6,000 tons of chemicals, including 3,998 tons of styrene, 1,027 tons of methyl ethyl ketone and 996 tons of isopropyl alcohol. On 30 October, in stormy weather, the vessel developed a list on its port side and its bow began to dip into the sea (Figure 1). At 08.00 hours, the 14-member crew (12 Italians and 2 Spaniards) were ferried to safety by a helicopter of the French Navy. A French tug was sent out to assist the abandoned vessel but could not get the tanker through heavy seas. The vessel sank in 60 - 80 metres of water, 18 km north-west of the Channel Island of Alderney, five hours before it was expected to reach the French port of Cherbourg (Figures 2, 3).

The ship was a 7,308 dwt double-hull chemical carrier fitted with 18 steel cargo tanks having a volume of 7,277 cu. m. The ship was built in 1989 and is registered in Italy, classed and operated by an Italian classification society and operated by an Italian company. During its life, the vessel had never changed flag.

The last expanded inspection had been carried out on 26 October 2000 and resulted in a detention of 3 days due to deficiencies related to the radio certification, lifesaving appliances, fire pumps and ISM Code implementation. None of these defective items were considered by the port state authorities as related to the classification society's responsibility.

Of the three products, styrene monomer is the chemical of most concern. Styrene is a colourless, oily, flammable liquid which has a sweet odour when pure and a sharp, disagreeable odour when impure. Like many monomers, styrene monomer is an extremely reactive and sometimes extremely unstable hazardous material that must be handled very carefully. Styrene can begin a potentially dangerous process called polymerization. In controlled polymerization, the liquid solidifies, expanding to about five times its original volume. Uncontrolled polymerization or "run-away polymerization" in a tank can be a violent exothermal reaction, powerful enough to rupture the tank, or in the extreme case, even burst the vessel, in a tank ship.

Styrene polymerizes at explosive rates at temperatures above 65ºC, a phenomenon which can cause the tank to rupture. Certain contaminants will readily form peroxides which, in turn, catalyze the polymerization reaction. To prevent this from happening, shipboard cargoes are usually stabilized with 10 to 15 parts per million (ppm) of an inhibitor called tertiary butyl catechol (TBC). However, even with the addition of an inhibitor, when heated above 51ºC, styrene can polymerize with the generation of so much heat that ignition is possible. A ship must therefore possess an inhibitor certificate before loading commences. This certificate indicates the amount and name of the inhibitor that has been added to the styrene monomer cargo; the date the inhibitor was added and its effective lifetime; any temperature limitations qualifying the inhibitor's effective lifetime; and details of action to be taken should the voyage length exceed the inhibitor's lifetime.

Due to its low electrical conductivity, styrene monomer can generate electrostatic charges when subject to agitation or particularly high flow rates. The substance reacts violently with strong oxidants and may be absorbed into the body by inhalation, ingestion or through the skin. It irritates the eyes, skin and respiratory tract, and, in liquid form, degreases the skin. Styrene is also harmful to aquatic life, having a 96hr-LC50 between 1 - 10mg/l. However, it is not a substance considered to bioaccumulate, but there is evidence to suggest that it will taint marine organisms.

The other two substances were methyl ethyl ketone and isopropyl alcohol. Methyl ethyl ketone is classified "D" according to the MARPOL 73/78 classification, i.e. if discharged into the sea, it would present a recognizable hazard to the marine environment. Isopropyl alcohol is classified "Class III", a flammable liquid, which is not considered toxic to the marine environment.

Furthermore, the tanker was carrying 160 tons of intermediate fuel oil and 40 tons of diesel. In case of leaks from the vessel, the fuel would probably form a slick that could contaminate the marine environment.

Resume

The response organisation worked well, probably much due to the Erika incident that happened less than a year before the Ievoli Sun. Both national and international co-ordination was trimmed during the Erika incident and one command centre was still operational. The technology used to salvage the styrene and the heavy fuel proved to be efficient .

After a complete survey of the wreck had been done it was decided that the most appropriate solution would be to pump up the styrene and the heavy fuel. The methyl ethyl ketone and the isopropyl alcohol could be released if monitored closely. This was done by a hired salvage team in April-May 2001. The release of methyl ethyl ketone and the isopropyl alcohol showed no evidence of environmental impact. The styrene and the fuel was pumped up with the help of a remote operated offloading system. Both air and sea samples were taken throughout the area during the operation but tests showed no traces of a styrene leak. The operation was finished in May 2001 .

In particular, some of the response measures carried out were as follows :

1) Using models, an initial exclusion zone of 2 km around the wreck was set up.

2) Air and sea observation: surveillance flights and sea patrols reported, for the most part, several coloured iridescences and some oil. An odour thought to be characteristic of styrene was initially detected in the air (4 November). On 13 November, in a surveillance flight, no signal was obtained using UV, IR and SLAR detection. On-site analyses conducted by the German vessel "Neuwerk" and the French vessel "Audacieuse" detected some styrene vapour presence in the air (maximum 2.5 ppm on 7 November). On 13 November, traces of trichloroethylene (<1 mg/m3) were detected 3 km west of the wreck. The last reports showed no significant traces of styrene in the atmosphere.

3) Surveillance of the wreck: the zone around the ship was marked off by four buoys set up by UK vessels. Video inspections using an ROV confirmed that the shipwreck came to lie on its port side on sand at a distance from the "Casquests" trench on a slight slope. It was considered unlikely that the wreck would slip towards the trench. Video inspections carried out on 10 and 11 November showed a stream of bubbles near the styrene tanks at the rear starboard side (Figure 4). The rate of loss was estimated at 30 litres/minute and 3 litres/minute on 10 and 11 November respectively. New video inspections are planned in view of analyzing the reasons for the leaks and to assess how these can be plugged.

The following vessels have participated in the two above mentioned operations:

- Northern Prince (UK), ROV support vessel;

- Neuwerk (Germany), specialized in combating chemical pollution at sea;

- Alcyon and Elan (France), pollution combating vessel on standby in the port of Cherbourg;

- Audacieuse, Versean, Lavallé and Iris (all French vessels), in charge of navigation;

- Gwen Drez (France), scientific analyses.

In addition, overflights have been carried out by British and French aircraft.

3) Behaviour of styrene: the behaviour of the styrene monomer on the water surface was studied under experimental conditions in ponds using a sample of the cargo which was supplied by SHELL. The study carried out by the Centre de Documentation de Recherche et d'Expérimentations sur les Pollutions Accidentelles des Eaux (CEDRE) showed that the vapour concentrations were lower than the detection limit of explosimeters (<10 ppm), although a strong odour of styrene could be detected. The study also showed that, after 18 hours, no styrene could be detected on the water surface which meant that no styrene could dissolve after this period. After 18 hours, the styrene partitioned as follows: 99.4% in air and 0.6% in water. Furthermore, the maximum concentration of dissolved styrene was 6 mg/l which was lower than the data reported in the literature. It was also observed that, just after 2 hours in water, the styrene formed micro-emulsions in water, but analysis showed that the micro-emulsions were composed of styrene monomer and that no polymerization took place.

There was also concern on the possibility of runaway polymerization of styrene monomer taking place in the tanks should water enter those tanks containing the product. The styrene had been dosed with 12 ppm of 4-tert-butylcatechol, equivalent to 48 kg/4,000 tons of styrene product. Accordingly, it was estimated that under the present temperature conditions of the sea, the inhibitor should be effective for at least seven months.

4)Protection of the coastline: as a precaution, booms had been pre-positioned at six strategic locations around the coast. From information in hand by the French authorities and tests carried out by CEDRE, it was concluded that a boom made of hypalon neoprene fabric with its components joined by a hot air weld would be more resistant to styrene than one made of neoprene fabric with its components glued together.

5) Protection of seafood resources: approximately 500 crustaceous baskets belonging to fishermen from Guernsey were pulled out from within the ban-on-fishing zone. Eco-toxicological tests were carried out by the British authorities. The "Neuwerk" removed some of these baskets and deep-froze them for future analysis. The analysis carried out so far indicated that the styrene concentrations in the crustaceans were all lower than the acceptable limits stipulated by the World Health Organization for seafood contaminated with styrene.

CEDRE has also set up a database with all the results of measurements and analysis concerning the accident which is updated daily. It has also launched experiments to evaluate the effects of a chronic release of styrene from the wreck.

6) Protection of human life: this aspect was dealt with on two fronts: the first dealt with precautions to take for the consumption of tainted seafood, the second dealt with the protective measures to be taken by response personnel and by the local population in the event of a large release of cargo. Regarding the first, it was suggested that the safety of consumers can be assured as long as tainted seafood is withdrawn for human consumption. According to the experts, the odour threshold for styrene is far lower than the concentration in seafood which would be considered to present a risk to the human population should contaminated seafood be consumed. Regarding the second, detailed instructions were prepared by the Poison Centre in Remes which listed the precautions to be taken by responders working at sea and those living along the coast in the event of a major release.