1984 - Brigitta Montanari

| Year | 1984 |

| Vessel | Brigitta Montanari |

| Location | Off Croatian Coast |

| Cargo type | Bulk |

| Chemicals | VINYL CHLORIDE inhibited or stabilized |

Summary

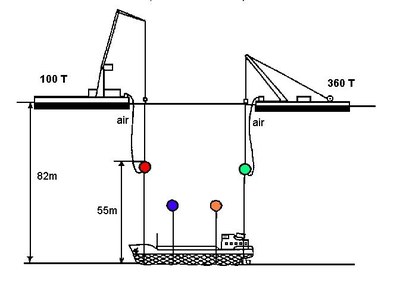

On November 16, 1984, the Italian gas carrier "Brigitta Montanari", carrying 1,300 tons of vinyl chloride monomer (VCM), sank in the Adriatic Sea in a depth of 82 metres off the coast of Croatia, on the outer rim of the Kornati National Park and nature reserve and 15 miles from the port of Sibenik (Figure 1).

The substance presents a dangerous fire hazard, being both extremely flammable and producing toxic fumes such as hydrogen chloride and phosgene. VCM vapour is heavier than air and is capable of travelling considerable distances and of being ignited by a remote ignition source. It is both a skin irritant and carcinogen. Inhalation of the vapour at high concentrations can have a narcotic effect and can reduce mental alertness while liquid VCM will cause cold burns on exposed skin. Ingestion of the substance is slightly harmful. VCM is often carried with a phenol inhibitor to prevent polymerization and ingestion of such a mixture is even more harmful.

Spontaneous polymerization is a severe problem when transporting VCM, especially over long distances. In practice, shorthaul cargoes such as those carried around N.W. Europe are not inhibited but on longhaul trades, it is considered vital. VCM will polymerize if exposed to heat, air, copper, aluminium or sunlight. A combination of light and air or an oxidizing agent can form explosive organic peroxides which catylze polymerization. Vapour cannot be inhibited, so any condensation may polymerize leading to blockages in pressure/vacuum valves or flame screens. The most appropriate fire fighting media are foam, dry powder or carbon dioxide. Water, if applied gently, may be used to blanket the surface of the cargo. Tanks should be kept cool with water to minimize the evolution of toxic decomposition fumes. In the event of a large spill, it may be advisable to blanket the spilt product with water or sand to minimize the vapour given off.

One consideration when carrying VCM in LPG tankers is the effect of the weight of the product during handling at sea. Incidents have been reported of vessels capsizing when undertaking tight manoeuvres, particularly when carrying VCM in deck tanks, since the centre of gravity is then significantly higher above the waterline than when trading lighter cargoes such as LPG or ethylene.

Narrative

On November 16, 1984, the Italian gas carrier "Brigitta Montanari", carrying 1,300 tons of vinyl chloride monomer (VCM), sank in the Adriatic Sea in a depth of 82 metres off the coast of Croatia, on the outer rim of the Kornati National Park and nature reserve and 15 miles from the port of Sibenik (Figure 1).

The substance presents a dangerous fire hazard, being both extremely flammable and producing toxic fumes such as hydrogen chloride and phosgene. VCM vapour is heavier than air and is capable of travelling considerable distances and of being ignited by a remote ignition source. It is both a skin irritant and carcinogen. Inhalation of the vapour at high concentrations can have a narcotic effect and can reduce mental alertness while liquid VCM will cause cold burns on exposed skin. Ingestion of the substance is slightly harmful. VCM is often carried with a phenol inhibitor to prevent polymerization and ingestion of such a mixture is even more harmful.

Spontaneous polymerization is a severe problem when transporting VCM, especially over long distances. In practice, shorthaul cargoes such as those carried around N.W. Europe are not inhibited but on longhaul trades, it is considered vital. VCM will polymerize if exposed to heat, air, copper, aluminium or sunlight. A combination of light and air or an oxidizing agent can form explosive organic peroxides which catylze polymerization. Vapour cannot be inhibited, so any condensation may polymerize leading to blockages in pressure/vacuum valves or flame screens. The most appropriate fire fighting media are foam, dry powder or carbon dioxide. Water, if applied gently, may be used to blanket the surface of the cargo. Tanks should be kept cool with water to minimize the evolution of toxic decomposition fumes. In the event of a large spill, it may be advisable to blanket the spilt product with water or sand to minimize the vapour given off.

One consideration when carrying VCM in LPG tankers is the effect of the weight of the product during handling at sea. Incidents have been reported of vessels capsizing when undertaking tight manoeuvres, particularly when carrying VCM in deck tanks, since the centre of gravity is then significantly higher above the waterline than when trading lighter cargoes such as LPG or ethylene.

Resume

The conclusions drawn from the risk environment of the authorities were that the VCM is toxic, flammable over a broad concentration, and carcinogenic. Due to its high volatility, its residence time on the water surface would be short.

However, when the sea is stratified (which is a common characteristic during the summer season) and the release takes place from deeper waters, the exchange with the atmosphere would be limited by the slow upward movement towards the sea surface of the product. This would increase the residence time of the substance in the water column. Furthermore, the solubility of vinyl chloride would also increase at lower depths due to an increase with pressure whilst any biodegradation would be slow in deep water. Possibly the only route for the effective removal of VCM from the marine environment would be through photolytic breakdown which would take place in the upper layers. These factors would have a bearing on the aquatic toxicity of the product.

Regarding the casualty, the authorities concluded that the window of opportunity to carry out a salvage operation would be short since the area was exposed to north and south winds. Furthermore, the wreck, which was lying at a depth of 82 metres, meant that a survey could only be undertaken by either deep sea divers or by submarine, hence making a detailed inspection of the wreck difficult at the time. The authorities were aware that the VCM was in four steel tanks which were able to endure pressures of 13.5 bar whilst the pressure inside and outside the tanks was about 3 and 9 bar respectively.

The options considered by the authorities in charge were:

- encasing the wreck in concrete on the sea bottom at the site of sinking;

- transforming the VCM into an inert product (PVC) by the addition of a polymerization initiator into the tanks;

- releasing the VCM by explosive destruction of the tanks;

- releasing the VCM in a controlled manner;

- pumping the VCM into another vessel from the depth of 82m; and

- raising the wreck to a depth of 30m and pumping the VCM into another vessel.

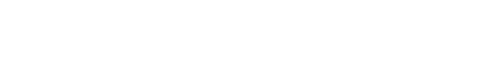

Given all considerations, the last option was considered the most appropriate. The wreck was first rightened since it lay on its starboard side and then was lifted to a depth of 30m and the VCM was recovered (Figure 2). When empty, the wreck was lifted to the sea surface and transported to a shipyard. A monitoring programme for VCM in the seawater and air was carried out until the wreck and its cargo were salvaged. Due to inclement weather and safety considerations, salvage operations started in the summer of one year, temporarily stopped during winter and completed the following spring of 1988.

During the initial stages of the salvage operation, VCM was detected at the sea surface as the wreck was being rightened on its keel. This led to the assumption that at least one of the tanks had been damaged and was releasing VCM. It was also suspected that some of the substance which had leaked out of the tank was trapped between the port side and the deck plating. In order to avoid a sudden release of a large quantity of VCM during the salvage operation, a hole was drilled into the deck plating, releasing the accumulated VCM. The initial release was quite intense. After several days and when the leak had subsided, PVC pipes were connected by divers to the drilled holes to carry the VCM to the sea surface, where it dispersed naturally or was burnt.