1989 - Perintis

| Year | 1989 |

| Vessel | Perintis |

| Location | English Channel |

| Cargo type | Package |

| Chemicals | CYPERMETHRIN , LINDANE , PERMETHRIN |

Summary

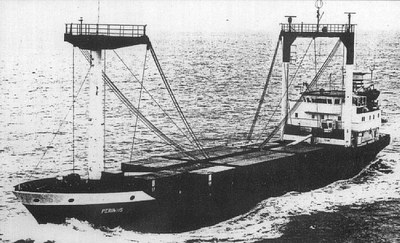

The M/V Perintis (Figure 1), an Indonesian owned and Panamanian registered cargo ship, was en route from Antwerp to Surabaya, Indonesia when it sank around mid-morning, 30 miles north-west of the Channel Islands (Figure 2) on March 13, 1989. The wind was west-by-north at 35 knots, gusting 40 to 45 knots, with a heavy swell and rough sea.

The sinking of the vessel was preceded by a mayday message from the master who reported a 35-degree list, 11 crew members on board and requested immediate assistance. British marine rescue services mobilized a co-ordinated search and rescue (SAR) operation. Despite an incorrect position from the distressed vessel, the 11-man crew was safety picked up by helicopters. One crew member later died in hospital. The SAR operation was completed by midday.

The Marine Pollution Co-ordinating unit was informed at 12.14 hours of the incident and immediately requested the Coast Guard to ascertain the vessel's cargo. The cargo manifest obtained from the shipping agent in Antwerp showed the presence of several consignments of chemicals likely to pose a threat to the marine environment:

- lindane 5.8 tonnes;

- permethrin 1.0 tonnes;

- cypermethrin 0.6 tonnes;

- dichlorodifluoromethane 18.5 tonnes.

Urgent enquiries were made of the survivors, the relevant chemical manufacturers in the U.K. and Europe, shipping agents and ports of loading to establish the exact form of the chemicals, their packaging and exact stowage on the Perintis. The following facts were established:

- lindane, a pesticide, was in 50 kilogram sealed polythene bags inside fibreboard drums (116) within a commercial 40-foot box container stowed on the upper deck;

- permethrin and cypermethrin pesticides, both in 50 kilogram sealed polythene bags contained within sealed 20 and 12 metal drums respectively, stowed on pallets in the hold;

- dichlorodifluoromethane, a CFC in liquid form, was in a tank container stowed on the upper deck.

The exact form of the pesticides and their stowage positions in the hold and on the upper deck were not yet known but enough information was available to make an initial assessment.

The lindane cargo caused the most concern. Lindane is one of the substances in the International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code grouped under the entry "Organochlorine pesticides, solid, toxic, NOS" UN No. 2761. Its oral toxicity level is such that it is designated as a Packing Group II substance and both on deck or under deck stowage is permitted. Lindane is also one of 366 chemicals listed as "extremely hazardous substances" by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and appears in List 1 substances under the E.C. directive on the discharge of dangerous substances to the marine environment. Effects on marine life may be expected at 100ng/l. It was estimated that an instantaneous release of 5.8 tonnes could theoretically generate levels up to 10mg/kg in fish flesh extending over an area of more than 300km2.

The permethrin and cypermethrin are extremely toxic to crustacean and fish and effects on marine biota may be expected to occur at concentrations of 10ng/l and over. Although re-population of an affected area by fin-fish could be rapid, crustaceans would take longer to recover. It was estimated that a full release could theoretically contaminate a very considerable area up to 40,000km2 to 1ng/l.

The conclusions drawn by the authorities following the initial hazard assessment were the following:

1) the general concern over the pesticides was for the possible scale of damage to fishing resources since the Perintis was lying in an important lobster and crab fishing ground;

2) the threat of pollution to the U.K. authorities was serious enough to warrant recovery of the lindane;

3) the permethrin and cypermethrin, although more toxic than lindane, were degradable in sea water and so were assessed as posing a lesser threat, but it was recommended that they should be recovered if practicable;

4) the dichlorodifluoromethane was deemed to pose no danger to the marine environment but in view of its potential hazardous properties if released in the atmosphere it was recommended that it should be recovered if the opportunity arose.

On the evening of March 13 at 17.30, 2 containers from the Perintis were sighted drifting into French waters.

Narrative

The M/V Perintis (Figure 1), an Indonesian owned and Panamanian registered cargo ship, was en route from Antwerp to Surabaya, Indonesia when it sank around mid-morning, 30 miles north-west of the Channel Islands (Figure 2) on March 13, 1989. The wind was west-by-north at 35 knots, gusting 40 to 45 knots, with a heavy swell and rough sea.

The sinking of the vessel was preceded by a mayday message from the master who reported a 35-degree list, 11 crew members on board and requested immediate assistance. British marine rescue services mobilized a co-ordinated search and rescue (SAR) operation. Despite an incorrect position from the distressed vessel, the 11-man crew was safety picked up by helicopters. One crew member later died in hospital. The SAR operation was completed by midday.

The Marine Pollution Co-ordinating unit was informed at 12.14 hours of the incident and immediately requested the Coast Guard to ascertain the vessel's cargo. The cargo manifest obtained from the shipping agent in Antwerp showed the presence of several consignments of chemicals likely to pose a threat to the marine environment:

- lindane 5.8 tonnes;

- permethrin 1.0 tonnes;

- cypermethrin 0.6 tonnes;

- dichlorodifluoromethane 18.5 tonnes.

Urgent enquiries were made of the survivors, the relevant chemical manufacturers in the U.K. and Europe, shipping agents and ports of loading to establish the exact form of the chemicals, their packaging and exact stowage on the Perintis. The following facts were established:

- lindane, a pesticide, was in 50 kilogram sealed polythene bags inside fibreboard drums (116) within a commercial 40-foot box container stowed on the upper deck;

- permethrin and cypermethrin pesticides, both in 50 kilogram sealed polythene bags contained within sealed 20 and 12 metal drums respectively, stowed on pallets in the hold;

- dichlorodifluoromethane, a CFC in liquid form, was in a tank container stowed on the upper deck.

The exact form of the pesticides and their stowage positions in the hold and on the upper deck were not yet known but enough information was available to make an initial assessment.

The lindane cargo caused the most concern. Lindane is one of the substances in the International Maritime Dangerous Goods (IMDG) Code grouped under the entry "Organochlorine pesticides, solid, toxic, NOS" UN No. 2761. Its oral toxicity level is such that it is designated as a Packing Group II substance and both on deck or under deck stowage is permitted. Lindane is also one of 366 chemicals listed as "extremely hazardous substances" by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and appears in List 1 substances under the E.C. directive on the discharge of dangerous substances to the marine environment. Effects on marine life may be expected at 100ng/l. It was estimated that an instantaneous release of 5.8 tonnes could theoretically generate levels up to 10mg/kg in fish flesh extending over an area of more than 300km2.

The permethrin and cypermethrin are extremely toxic to crustacean and fish and effects on marine biota may be expected to occur at concentrations of 10ng/l and over. Although re-population of an affected area by fin-fish could be rapid, crustaceans would take longer to recover. It was estimated that a full release could theoretically contaminate a very considerable area up to 40,000km2 to 1ng/l.

The conclusions drawn by the authorities following the initial hazard assessment were the following:

1) the general concern over the pesticides was for the possible scale of damage to fishing resources since the Perintis was lying in an important lobster and crab fishing ground;

2) the threat of pollution to the U.K. authorities was serious enough to warrant recovery of the lindane;

3) the permethrin and cypermethrin, although more toxic than lindane, were degradable in sea water and so were assessed as posing a lesser threat, but it was recommended that they should be recovered if practicable;

4) the dichlorodifluoromethane was deemed to pose no danger to the marine environment but in view of its potential hazardous properties if released in the atmosphere it was recommended that it should be recovered if the opportunity arose.

On the evening of March 13 at 17.30, 2 containers from the Perintis were sighted drifting into French waters.

Resume

On the same day of the incident, March 13, a vessel left from Southampton to locate and buoy the wreck. This was duly completed by the next day.

Also on the evening of March 13, the French authorities were informed of 2 containers sighted drifting into French waters. Details of the cargo were included with the information sent.

On the morning of 14 March, the French authorities mounted an intensive air and sea search within their sector to locate and track the floating containers because they were a danger to navigation. They were also requested to check the serial numbers of the containers to determine whether the lindane container had floated free since the cargo manifest had identified the lindane container by the serial number painted at its ends. Some 9 containers were now believed to be adrift in the French sector.

The French authorities invoked the Mancheplan Agreement, an Anglo-French Joint Maritime Contingency Plan for dealing with incidents in the Channel during peacetime. This action was taken because it was assessed that the lindane container was on the French side of the Mancheplan median line. Accordingly, MARINE CHERBOURG became the Action Co-ordination Authority (ACA) responsible for co-ordinating joint operations and requested that MPCU assume the duties of Action Liaison Authority (ALA), responsible for co-ordinating the provision of assistance to the ACA. MPCU agreed.

Also on March 14, a pollution report was issued to all Bonn Agreement Contracting Parties, the first in a series to keep them informed of events and progress.

By this stage, it was established that neither the owner nor the cargo owners intended to take any action in respect of the vessel or its cargo. The U.K. Secretary of State intervened under the International Convention Relating to Intervention on the High Seas wherein a Contracting Party is empowered to take action in relation to a foreign registered vessel outside a Contracting State's territorial water to protect its waters against a grave and imminent danger of large scale pollution.

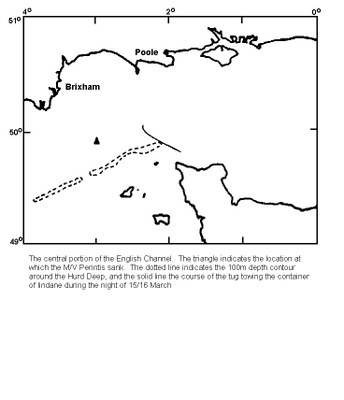

In the afternoon of March 15, the lindane container was located floating to the north of the Channel Islands. A French naval tug attached a line to this container and began towing it towards Cherbourg. However, in the continuing bad weather, the towline parted sometime during the night of the 15/16 March and the container was lost in the vicinity of the Hurd Deep (Figure 2), to the north-east of Alderney. Initially, it was not known whether container sank or remained afloat after the tow was lost, but attention was focussed on its likely movement if afloat. Drift simulations using a computerized water transport model suggested the likely movement to north and east towards the Strait of Dover (Figure 3), but the exact release position would be critical to the outcome of the modelling of the drift, as it is possible for a parcel to be caught in a gyre to the north of the Channel Islands (track A, Figure 3) rather than be carried to the east. Eventually, the inference of the report was that the container had sunk in an undamaged state. The position was well inside the French sector, therefore relocation and recovery remained a French responsibility.

On March 20, the French authorities instituted a ban on anchoring, dredging and trawling in an area 12km2 around the presumed site of the lost container. This was primarily to prevent vessels operating in the area from hampering the search for the container. The French authorities also decided to commence water and fish sampling to check if there were any increased traces of lindane. This continued for several weeks. The lindane container was never found, and over a longer period of time, checks of water and fish sampling did not show notable increases in background traces of lindane.

On March 21, the U.K. authorities applied a precautionary fishing ban in an area of radius 12km around the presumed position of the lost container and prohibited both fishing in the area and the landing or sale in the U.K. of fish caught in the prohibited area. These controls did not extend to the Channel Islands in respect of fish landed at ports other than in the U.K.

A meeting of Anglo-French experts was held on 4 April in Cherbourg, at which the original assessment of the threat posed by the unrecovered lindane to marine resources and human consumers was reconsidered in the light of studies conducted in the two countries since the sinking of the Perintis and of the loss of the container carrying the lindane. Their summary was as follows:

1) analyses conducted to date showed no tangible sign of pollution by lindane;

2) a concentration of 100ng/1 in sea water would indicate that release of the compound had occurred;

3) the maximum bioconcentration factor for fish is 1000 times. Thus, a concentration of lindane of 1(g/l would lead to a concentration in fish flesh of about 1mg/kg, or 1000 times higher than both the concentrations found in these studies and background studies carried out prior to the incident. Even these values would be less than those permitted by British and French authorities;

4) sampling should continue. If concentrations of 1mg/kg were to be observed, they would indicate contamination, but not until higher concentrations were detected (a few milligrams per kilogram), would they represent any risk to even regular consumers of fish from the affected areas.

The controls imposed by both the French and U.K. authorities remained in force until April 7 when the search for the lindane container was abandoned, since by that time, more detailed assessment of the actual risks posed to consumers had taken account of the true local conditions and likely dissolution rates rather than assumed the worst circumstances.

Meanwhile, under a geographical split of the responsibility agreed previously between the French and U.K. authorities, the Marine Pollution Control Unit (MPCU) of the U.K. was co-ordinating a survey of the wreck, as and when weather permitted, to determine the practicability of recovering the permethrin and cypermethrin. These compounds were carried in the No. 1 hold of the Perintis and were presumed to be in or near to the wreck.

Poor weather delayed the start of operations, but by March 29, a vessel was on site and a remotely operated vehicle had established that the hatch covers of the ship were missing and that at least some of the cargo was scattered on the sea bed adjacent to the wreck. Visibility at the site of the wreck was poor, sometimes as low as 0.6 metres. Despite these difficulties, five drums had been located on the sea bed by March 31. A number of sonar contacts, consistent with the presence of other drums, were made by a Royal Navy minesweeper, but these could not be confirmed at the time.

Discussions between the competent fisheries and the MPCU confirmed the desirability of recovering as many drums as possible from the sea bed, even though the chemical companies Rhone Paulenc Agro Chemie of Lyon and the Wellcome Foundation of the U.K. advised that the metal drums would not float and that they had a life expectancy of at least one year in sea water, after which they would begin to corrode and release their contents. The maximum concentration reached in sea water would be dependent on the rate of solution and experiments were undertaken in "flow-through" tank systems to establish what this might be in sea water at the temperatures prevailing in the English Channel in April. When the recovery operation was terminated on April 23, all twelve drums of cypermethrin and sixteen of the twenty drums of permethrin had been recovered, along with the tank of dichlorodifluoromethane which had also been carried in the hold. All the recovered chemicals from the sea bed were collected for disposal by the manufacturers concerned.

One of the drums of permethrin recovered was transported to a government laboratory where experiments on the dissolution rate were repeated with the actual batch of cargo. The physical state of the permethrin recovered from the sea bed proved to be a waxy solid with a much slower rate of dissolution than had been assumed in initial hazard assessments. Calculations suggested that exposure of the contents of one drum would result in concentrations exceeding 1 ng/l over an area of <0.25km2, and that the area within which fish, shellfish or their larvae would be damaged would probably be <0.03km2. These areas were considered to be insignificant and further search and recovery of the remaining drums was considered to be unjustifiable.