1996 - Igloo Moon

| Year | 1996 |

| Vessel | Igloo Moon |

| Location | Cape Florida, USA |

| Cargo type | Bulk |

| Chemicals | BUTADIENES inhibited |

Summary

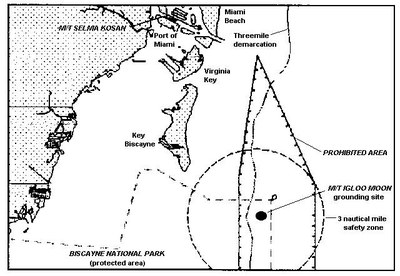

On the morning of November 6, 1996 the LPG tanker M/T Igloo Moon stranded on a coral reef 5.5 km south-southeast of Cape Florida on the boundary of Biscayne Bay National Park (Figure 1). The stranding took place in close proximity to areas of dense population and high recreational use. Butadiene is shipped refrigerated with a chemical inhibitor added for greater stability and to prevent polymerization and oxidation. The vessel's cargo was 6589 metric tons of butadiene; the ship also carried 205 metric tons of intermediate fuel oil; 108 metric tons of diesel fuel and 22 tons of lube oil.

Butadiene has a tendency to absorb oxygen, resulting in the formation of peroxides and the initiation of polymerization of butadiene. Experience has shown that when not refrigerated, butadiene may heat at a rate of 15 - 20ºC per minute to temperatures exceeding 93oC while at the same time achieving pressure of 1 to 1.2 kbar. Under such conditions, explosion may occur. To transport butadiene safely aboard, it is stabilized in two ways: 1) the cargo is maintained below -4ºC and an inhibitor tert-butyl catechol (TBC), an antioxidant, to prevent auto-oxidant and polymerization is added. Another main hazard is that of flammability. At 21ºC, butadiene has a vapour pressure of 248.9 kPa (2.49 bar) and explosion limits between 2 and 12%. On numerous occasions, flammable butadiene clouds have ignited and flashed back to the source of the release, causing explosions that have contributed to much loss of life. Although acute toxicity can result from exposure to high concentrations of butadiene, at these concentrations, the risk from fire and explosion would be far greater than toxicity concerns. Data does however suggest that chronic exposure to butadiene may cause cancer.

Narrative

On the morning of November 6, 1996 the LPG tanker M/T Igloo Moon stranded on a coral reef 5.5 km south-southeast of Cape Florida on the boundary of Biscayne Bay National Park (Figure 1). The stranding took place in close proximity to areas of dense population and high recreational use. Butadiene is shipped refrigerated with a chemical inhibitor added for greater stability and to prevent polymerization and oxidation. The vessel's cargo was 6589 metric tons of butadiene; the ship also carried 205 metric tons of intermediate fuel oil; 108 metric tons of diesel fuel and 22 tons of lube oil.

Butadiene has a tendency to absorb oxygen, resulting in the formation of peroxides and the initiation of polymerization of butadiene. Experience has shown that when not refrigerated, butadiene may heat at a rate of 15 - 20ºC per minute to temperatures exceeding 93oC while at the same time achieving pressure of 1 to 1.2 kbar. Under such conditions, explosion may occur. To transport butadiene safely aboard, it is stabilized in two ways: 1) the cargo is maintained below -4ºC and an inhibitor tert-butyl catechol (TBC), an antioxidant, to prevent auto-oxidant and polymerization is added. Another main hazard is that of flammability. At 21ºC, butadiene has a vapour pressure of 248.9 kPa (2.49 bar) and explosion limits between 2 and 12%. On numerous occasions, flammable butadiene clouds have ignited and flashed back to the source of the release, causing explosions that have contributed to much loss of life. Although acute toxicity can result from exposure to high concentrations of butadiene, at these concentrations, the risk from fire and explosion would be far greater than toxicity concerns. Data does however suggest that chronic exposure to butadiene may cause cancer.

Resume

Early surveys of the grounded ship revealed that the bottom had been holed and several double-bottom tanks were breached. The authorities began evaluating chemical hazard information, resources at risk, and protection priorities and strategies. Evaluation of the chemical properties of butadiene indicated that the major concern was the inherent flammability of the product. The reactivity of butadiene was also a concern, however the safety features present (see below) were sufficient to consider this factor as minimal. Because of the moderate toxicity of butadiene, only a large release would have required the evacuation of beach communities. The authorities defined three probably release scenarios: entire release of the cargo at a rate of 100 tons/minute (worst case scenario) 1000 ton release at a rate of 10 tons/minute (most probable scenario); 1 ton/minute (small spill) and factored in the explosion possibility in each scenario. Based on these scenarios, a plan was devised to address issues such as: evacuation, sheltering, alert and notification, protecting people with special needs.

By November 8, lightering of fuel had been accomplished and only enough diesel fuel was left aboard to continue the operation of necessary ship systems, including the critical refrigeration of the butadiene cargo. As a result of an approaching storm weather system, the stability of the cargo became a serious concern due to the lack of information on the efficacy of the chemical inhibitor since the certificate for the inhibitor was due to expire on November 9. Fresh inhibitor was sent on-scene to be added but the option to have the cargo tested was chosen as opposed to potentially ruining it by adding more inhibitor. Based on tests, the inhibitor was re-certified to December 1, 1996.

Salvors calculated that approximately 1500 metric tons of butadiene would need to be offloaded in order to refloat the vessel. Ship-to-ship transfer (STS) was the method chosen for lightering the vessel. A butadiene-certified tank ship that could navigate the coral reefs and shallow waters at the grounding site was found. A hydrographic survey was conducted around the site to determine the best routes for sufficient bottom clearance for both vessels during the salvage operation and mark best entry and exit channels and shallow areas to avoid within the channel.

The salvage operations also required that seas be no greater than one metre during the operation while the ships were moored together and the cargo transferred. Due to the gale storm, the hydrographic survey and subsequent salvage operations were delayed by several days.

Once salvage operations resumed, the salvage plan required not only lightering a portion of the cargo but also deballasting of the ballast tanks in order to get the ship light enough to refloat. The National Park Service was concerned that the release of ballast water into the park might introduce toxic pollutants or introduce some exotic invasive species possibly picked up during the ships' overseas transit. Examination of the ballast records showed that this was possible. Following consultation, chemical treatment was deemed to be the option to ensure that non-indigenous biota would not be released alive. Chlorination was the likely option since chlorine oxidizes or "burns" the cell walls and gets used up in the process (i.e. breaks down into a less toxic form). Calcium and sodium hypochlorites are commonly used as disinfectants and bleaching agents. The most easily available reagent was calcium hypochlorite [(Ca(OCCl2)]: a whitish powder containing about 65% available chlorine (the active killing ingredient). With water, it reacts to form calcium hydroxide and hypochlorous acid, the active ingredient. However, the material is extremely corrosive and becomes extremely hot and can explode when mixed with anything organic, e.g. paper, oil, skin, petroleum products etc. Experience has shown that chlorine concentrations in the range of 25 - 100 ppm (as chlorine) are required to kill all marine organisms with a "soak" of several hours. It was estimated that at the time and points of deballasting, chlorine concentrations would be no greater than 10 ppm, quickly diluting to non-hazardous concentrations near the ship.

Instructions were given to dilute the calcium hypochlorite powder in stock solutions and then feed the solutions through tubes in each tank. Ballast tanks were either treated with 100 ppm for 2 hours or 50 ppm for 12 hours. On November 21, 15 days after it had run aground, the Igloo Moon was refloated.