1987 - Herald of Free Entreprise

| Year | 1987 |

| Vessel | Herald of Free Entreprise |

| Location | Zeebrugge, Belgium |

| Cargo type | Package |

| Chemicals | ACRYLONITRILE inhibited , ANILINE , ANTIMONY PENTAFLUORIDE , CHLORINE , DIETHYL ETHER , ETHYLENE (compressed gas) , ETHYLENE (refrigerated liquid) , HYDROGEN BROMIDE , METHYLAMINE anhydrous , TOLUENE DIISOCYANATE |

Summary

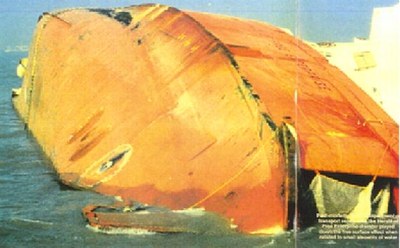

On March 6, 1987, the British car ferry Herald of Free Enterprise of Townsend Thoreseen sank off the Belgian harbour of Zeebrugge, causing the loss of about 200 lives. The ship had heeled over just a few minutes after leaving port and was lying on its side in ten-metre water depth (Figure 1). After the initial rescue operation, the recovery of the vessel and its cargo was considered urgent due to the presence on board of five lorries carrying dangerous goods. A first list of these was made available to the authorities twelve hours after the accident. The list was incomplete and inaccurate; for example, one lorry was described to be carrying soluble lead compounds which is quite an incorrect description of tribasic lead sulphate which is very insoluble in water. The full manifest with a summary of the entire cargo was obtained 73 hours after the disaster. Out of five lorries with dangerous goods, three had waybills lacking essential information. In one case, the description was so inaccurate that even after additional information had been supplied by the shipper, it remained impossible to make out what precisely was on the lorry. A large amount of work was required to verify the nature and the precise physical state (solid, liquid or solution, etc.) of the substances, their location on board, the type of package or container and its likely behaviour in water and how each package could be identified. An inventory of the dangerous cargo based on the documents made available to the Belgian authorities and on the salvage cargo are shown below:

Lorry A:

- Toluene di-isocyanate in solution (25 drums of 218 kg each).

Lorry B:

- cyanide-containing wastes (2 drums of 200 litres each; 3 drums of 120 litres each);

- cyanide-containing hardening salts (1 drum of 200 litres);

- cyanide-containing liquid (30 litre drum; quantity of drums unknown);

- chlorine trifluoride + fluorine perchlorate (8 gas cylinders of 30 litres each and 2 gas cylinders of 10 litres each);

- twelve chemicals (hydrogen bromide, chlorine, ethylene, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen chloride, fluoromethane, diethyl ether, chlorotrifluoromethane, methylamine, tetrafluoroborate, antimony pentafluoride) in 21 gas bottles ranging in size from 0.1 to 0.5 litres;

- chemicals (52 different chemicals were reported) in 180 buckets ranging in size from 12 to 30 litres;

- paint wastes (40 drums of 200 litres each).

Lorry C:

- Hydroquinone (200 paper sacks of 2 kg each wrapped in polyethylene sheeting).

Lorry D:

- leatherpaint (35 drums of 100 kg each);

- leatherpaint agent containing methoxyethanol toulene (15 drums of 100 kg each);

- leatherpaint diluent (5 drums of 10 kg each).

Lorry E:

- Granulated tribasic lead sulphate (20 pallets of forty 25 kg paper sacks wrapped in polyethylene sheeting).

Lorry A had fallen overboard as the ferry heeled over. It had been pulled out of the water empty: the drums of toluene di-isocyanate were therefore lost at sea. Lorry B was visible on B deck at low tide and only some of its chemical cargo had been spilled. Lorry C with the hydroquinone was deep in the E deck garage and could not be dealt with before the ferry was uprighted. Lorry D had also fallen overboard and only the cab of the lorry had been recovered. Drums of leatherpaint were adrift, but some had quickly been picked up. Lorry E was deep in the hold on B deck and not visible: the condition of the lead sulphate was unknown.

Narrative

On March 6, 1987, the British car ferry Herald of Free Enterprise of Townsend Thoreseen sank off the Belgian harbour of Zeebrugge, causing the loss of about 200 lives. The ship had heeled over just a few minutes after leaving port and was lying on its side in ten-metre water depth (Figure 1). After the initial rescue operation, the recovery of the vessel and its cargo was considered urgent due to the presence on board of five lorries carrying dangerous goods. A first list of these was made available to the authorities twelve hours after the accident. The list was incomplete and inaccurate; for example, one lorry was described to be carrying soluble lead compounds which is quite an incorrect description of tribasic lead sulphate which is very insoluble in water. The full manifest with a summary of the entire cargo was obtained 73 hours after the disaster. Out of five lorries with dangerous goods, three had waybills lacking essential information. In one case, the description was so inaccurate that even after additional information had been supplied by the shipper, it remained impossible to make out what precisely was on the lorry. A large amount of work was required to verify the nature and the precise physical state (solid, liquid or solution, etc.) of the substances, their location on board, the type of package or container and its likely behaviour in water and how each package could be identified. An inventory of the dangerous cargo based on the documents made available to the Belgian authorities and on the salvage cargo are shown below:

Lorry A:

- Toluene di-isocyanate in solution (25 drums of 218 kg each).

Lorry B:

- cyanide-containing wastes (2 drums of 200 litres each; 3 drums of 120 litres each);

- cyanide-containing hardening salts (1 drum of 200 litres);

- cyanide-containing liquid (30 litre drum; quantity of drums unknown);

- chlorine trifluoride + fluorine perchlorate (8 gas cylinders of 30 litres each and 2 gas cylinders of 10 litres each);

- twelve chemicals (hydrogen bromide, chlorine, ethylene, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, hydrogen chloride, fluoromethane, diethyl ether, chlorotrifluoromethane, methylamine, tetrafluoroborate, antimony pentafluoride) in 21 gas bottles ranging in size from 0.1 to 0.5 litres;

- chemicals (52 different chemicals were reported) in 180 buckets ranging in size from 12 to 30 litres;

- paint wastes (40 drums of 200 litres each).

Lorry C:

- Hydroquinone (200 paper sacks of 2 kg each wrapped in polyethylene sheeting).

Lorry D:

- leatherpaint (35 drums of 100 kg each);

- leatherpaint agent containing methoxyethanol toulene (15 drums of 100 kg each);

- leatherpaint diluent (5 drums of 10 kg each).

Lorry E:

- Granulated tribasic lead sulphate (20 pallets of forty 25 kg paper sacks wrapped in polyethylene sheeting).

Lorry A had fallen overboard as the ferry heeled over. It had been pulled out of the water empty: the drums of toluene di-isocyanate were therefore lost at sea. Lorry B was visible on B deck at low tide and only some of its chemical cargo had been spilled. Lorry C with the hydroquinone was deep in the E deck garage and could not be dealt with before the ferry was uprighted. Lorry D had also fallen overboard and only the cab of the lorry had been recovered. Drums of leatherpaint were adrift, but some had quickly been picked up. Lorry E was deep in the hold on B deck and not visible: the condition of the lead sulphate was unknown.

Resume

While the owner of the ferry retained his rights and remained responsible for salvaging the ship, the Belgian State assumed control of operations. For the authorities, the concerns were humanitarian (rescue of trapped people), salvage, recovery of property (cargo), environmental (incorporating an evaluation of the hazards of the cargo to people and to the environment, environmental monitoring and taking protective measures to mitigate pollution effects), navigational (freeing the waterway for navigation) and judicial.

Once the human aspect was dealt with, there was a need to integrate the counter-pollution activities in the salvage operation which meant a variety of simultaneous operations being carried out requiring co-ordination. This was complicated due to the conflicting interests of the State and the ship owner and due to a lack of understanding of the environmental implications of the situation by some of the parties involved. Decisions were taken by a committee where all the parties involved were represented. Thus the work of the salvage company was co-ordinated with the retrieving of the dead bodies, the judicial enquiry on board and ashore, the search and recovery of the dangerous cargo, environmental monitoring and counter-pollution activities. At each step of the operation, consensus had to be reached on priority setting and ensuring that these activities were made compatible.

For the owner, the main concern was the salvage of the vessel in the shortest possible time and at a minimum cost. The salvage company's interest was to use simple, efficient re-floating techniques with as little outside interference as possible. As soon as the initial rescue operation was over and the presence of the dangerous cargo was known, the authorities announced their intention to lay certain requirements in relation to counter-pollution measures and to monitor the water quality. The ship owner went to court against the State, out of fear that the proposed measures could interfere with the salvage of the ship. The court appointed an independent expert and instructed him to reconcile points of views. All decisions relating to environmental protection were thereafter made under court supervision. This slowed down the procedure initially since the State had to use persuasion rather than its authority to implement an action. It however gave the advantage that the ship owner would not contest a decision once this was agreed to.

Re-floating the ferry took 52 days. Work was interrupted after six days by bad weather, sometimes for several days. The salvage vessels succeeded in uprighting the ship on April 7, holding her dynamically in position, but then had to let her go as a storm was building up. The ship was uprighted again later, holes plugged, water pumped out and the ship taken back to port on April 27.

An evaluation of the exact nature, hazard and situation of the dangerous cargo had to be made. In the first hours, some basic information on the properties of the chemical was supplied by a data centre belonging to the Ministry of Interior. A number of other sources were then consulted, including the GESAMP hazard profiles and the IMDG Code. A first evaluation was completed on March 8. An important factor considered in the evaluation was the reaction and degradation products of the chemicals once spilled into the marine environment. Under the circumstances, the chemicals of concern were: the degradation product of hydroquinone, quinone and the hydrolysis product of toulene di-isocyante, toulene diamine.

An assessment of the actual danger could only be arrived to by simulating the likely behaviour of the goods after their release at sea and by the actual monitoring of the environment to detect the presence of the chemicals.

A simplified scenario was used to quickly calculate the extent of the sea area in which concentrations considered lethal for marine organisms could be reached. The scenario assumed immediate and uniform dispersion of the quantity of each chemical that remained unaccounted for over an average depth of 10 metres. Literature values were used as guides in these estimates. According to the estimates, except the hydroquinone, none of the substances could cause real problems beyond 165 metres from the source. It was thought that the greatest risk was to people who handled a package, i.e. drums, tanks, buckets, etc. It was therefore important to locate and recover these packages.

For hydroquinone, the calculation indicated the possibility of a hazardous plume in the water column extending for more than 2 km from the source. A more precise evaluation was therefore needed. Using a dispersion model, a series of mathematical simulations on computer were made to study the fate of the substance in relation to the water mass as affected by the change in tide.

A real-time simulation using the actual meteorological forecast was run when the ferry was uprighted because it was feared that the cargo would shift and spill. However, the environmental monitoring results showed that the hydroquinone had probably dissolved away during the stormy weather.

Oil was being released from the vessel's vent pipes. An oil-fate model was therefore run to determine the drift of oil slicks. An attempt was made to adapt the model to simulate the drift of floating drums, but this was not considered useful since there was uncertainty about the immersion/emersion ratio of the lost packages while the geometry of each package was also thought to have a bearing on the drift. No model was available to simulate the behaviour of drums lying on the seabed. To gain some insight on the drift of the drums containing toulene di-isocyanate, a tracking experiment was carried out. This involved releasing a drum equipped with a transmitter at the point where the original drums had been lost and following its movement. Due to variable meteo-oceanographic conditions, this gave little, if any, useful results.

The environmental monitoring pursued two main objectives: to detect the presence of dangerous substances in the air or water inside the wrecked vessel in order to ensure the safety or personnel involved in the operation, and to assess the extent and impact of a spillage in the marine environment. Safety inside the casualty was the concern of both the salvage company and the governmental authorities, the latter having to conduct the judicial inquiry on board and to recover the remaining victims. Air and water samples were therefore taken by both parties and analyzed separately. A state-owned oceanographic vessel provided a platform for on-site monitoring, and a portable-laboratory housed in a container was installed in Zeebrugge harbour. Gas measurements (cyanide detection and explosimetry) were carried out inside the casualty. The quantity of cyanide in the cargo was small, but because of the presence of unidentified acids on the same lorry, the formation of deadly cyanohydric acid could not be excluded. Cyanides in the water were also analyzed on board the oceanographic vessel. Hydroquinone measurements were also made. Samples were dispatched every day to three state laboratories for validation of the field results.

A number of actions were decided upon to mitigate pollution effects. They included arrangements for oil containment and recovery, recovery of the lost packages, locating and securing the dangerous goods on board and securing the remaining cargo on board. An exclusion zone for ships and aircraft was imposed by the state to facilitate the operation. The position of the authorities was that first-line protective measures were the responsibility of the ship owner. These needed to satisfy the requirements laid down by the administration. The State insured a second line of defence by keeping vessels and equipment on stand-by, by supervising the operation, and by assisting in the search and recovery of lost cargo.

Absorbent material in 4 metre boom sections was laid inside the ferry to retain leaking fuel. A net was fastened to the structure across the gaping opening of the open garage to prevent parcels and wrecks from escaping (see Figure 1). A debris-retention net and an oil boom were deployed downstream of the casualty during the uprighting operation in order to contain oil and catch floating objects. Very little oil escaped from the ship and in fact none was recovered at sea. No oil dispersants were used. Little could be done to remove the cargo from the ferry before it was re-floated and towed back into the harbour: only a few gas cylinders were located and removed while the vessel was at sea.

All vessels on scene participated in the recovery of floating objects. Navy minesweepers and salvage tugs performed the search for sunken objects, but in spite of an intensive survey of the Zeebrugge ship channel and the surrounding area, only seven of the 25 drums containing toulene di-isocyanate were recovered. One major difficulty was to sort out the various items among the recovered cargo and to recognize those containing harmful products. Labels peel off and drum markings quickly become unreadable in sea water. A full and precise description of the appearance of both the dangerous and other packages would have been useful, but in many cases it was unavailable. It required a considerable amount of time and organizing to keep an accurate inventory of the recovered cargo and to verify the contents of suspicious containers. It was essential to keep an updated inventory of the dangerous substances in order to assess the danger to the marine environment by those not recovered. By the end of the operation, about half of the dangerous cargo had been recovered:

- toluene di-isocyanate (7 drums out of 25);

- cyanide containing wastes (1 drum out of 5);

- cyanide containing hardening salts (no drums recovered);

- cyanide containing liquid (1 drum);

- chlorine trifluoride + fluorine perchlorate (4 gas tanks, some empty, out of 8);

- 21 gas bottles containing different (12) chemicals (10 out of 21);

- 180 buckets containing 52 different chemicals (95 buckets out of 180);

- paint wastes (30 drums out of 40)

- hydroquinone (none);

- leatherpaints (26 drums out of 35);

- leatherpaint agent with MET (13 drums out of 15);

- leatherpaint diluent (3 drums out of 5);

- tribasic lead sulphate (all 20 pallets).